‘Father of Web3’ Explains: What Exactly Is Web3?

What Is Web3?

If you’re scratching your head over this question, you’re not alone. Despite the buzz from venture capitalists, media, and corporate announcements, Web3 remains a tough concept for most people to wrap their minds around.

At its core, Web3 refers to a decentralized online ecosystem built on blockchain technology. On a grander scale, it’s seen as the next phase of the internet—or perhaps even the next stage of human society. That is, if you buy into the vision.

The term “Web3” was coined in 2014 by Gavin Wood, co-founder of Ethereum, originally styled as “Web 3.0.”

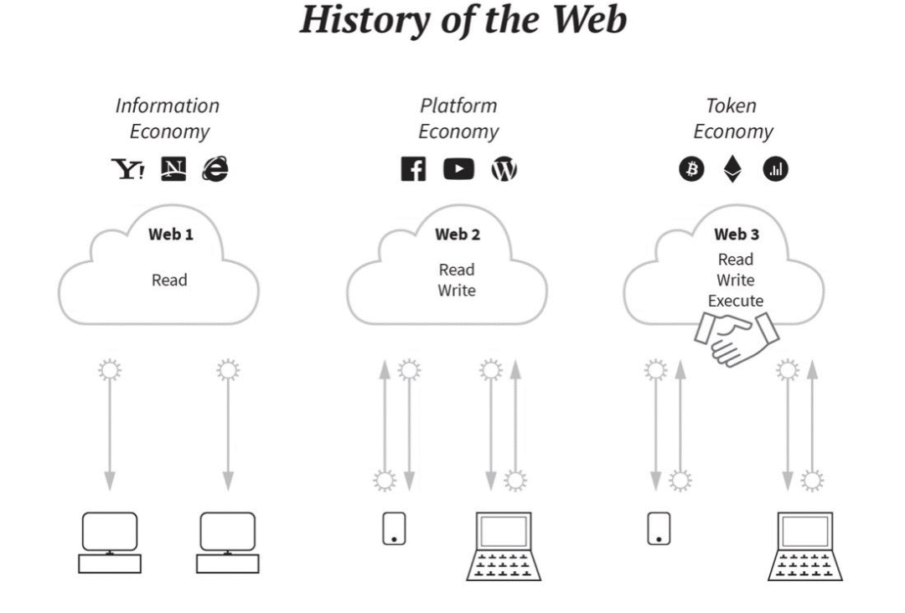

Since it’s Web 3.0, it implies predecessors: Web 1.0 and Web 2.0. Web 1.0, a relic of the past, was defined by static webpages with limited interactivity. Web 2.0 is our current era, dominated by centralized platforms owned by tech giants like Google, Meta, and Amazon, where much of our communication and commerce takes place.

From this perspective, Web3 envisions breaking this monopolistic control. Web3 platforms and apps, built on blockchain, aren’t owned by corporate giants but by users who gain ownership by contributing to the development and maintenance of these services.

To advance this vision, Gavin Wood leads the Web3 Foundation, which supports decentralized tech projects, and Parity Technologies, a company focused on building blockchain infrastructure for Web3, notably the Polkadot project.

In a recent interview, Gavin, as the originator of Web3, shared his perspective on what Web3 is and his outlook for its future. We’ve distilled the key points to help readers in this space gain clarity.

About Gavin Wood: A British computer scientist and Ethereum co-founder, Gavin was the primary developer of Ethereum’s C++ client prototype, authored the Ethereum Yellow Paper, and created Solidity, a programming language for Ethereum smart contracts. Dubbed Ethereum’s “invisible brain,” he proposed Web 3.0 post-Snowden leaks, envisioning an internet where individuals control their digital identity, assets, and data.

01 Why Do We Need Web3?

Gavin argues that the Web 2.0 model mirrors pre-internet societal structures, and Web3 exists because Web 2.0 falls short.

Rewind 500 years, and most people’s lives were confined to their villages or towns, interacting and trading only with known contacts. Social structures ensured trust in transactions—like expecting apples you bought wouldn’t rot quickly—because reputation mattered. Back then, moving between towns was tough, costly, and time-consuming, so people prioritized maintaining their credibility.

In simple terms: Web 1.0 was a read-only internet, Web 2.0 is a read-write internet, and Web3 promises a read-write internet without intermediaries—a decentralized web.

As societies grew into cities, nations, and global organizations, ensuring trust at scale required powerful, regulated institutions. These entities, in theory, exist to meet our expectations. For example, to operate in certain industries, you must meet legal requirements.

But this isn’t ideal. Emerging industries are hard to regulate because governments move slowly, often lagging behind innovation. Regulators aren’t perfect, especially when cozy relationships form between industries and oversight bodies. And their effectiveness is limited by resources, catching only the most blatant offenders, with varying standards across countries.

“We need to move beyond this,” Gavin says. “Unfortunately, Web 2.0 is stuck in this highly centralized model.”

“It’s a broken model,” he adds. “We need to fix this regulatory failure through technology.”

02 Less Trust, More Truth

To sum up Web3 in one sentence, Gavin calls it “less trust, more truth.”

In his view, “trust” has a specific meaning: it’s essentially “faith.” It’s a belief that something will happen or the world will work a certain way without solid evidence or rational backing.

In contrast, “truth” means having stronger reasons to believe expectations will be met.

Going further, Gavin sees “trust” as inherently problematic. Trust means granting power to others or organizations, who can wield it arbitrarily. This can lead to blind trust, which isn’t true trust at all.

03 Can We Break the Monopoly?

A key Web3 goal is dismantling monopolies, particularly those of platform giants like Google and Meta.

Gavin admits this sounds daunting and isn’t sure if it’s fully achievable, but he believes it’s a logical improvement—and unavoidable unless “human society is heading toward decline.”

He points to encryption as an example. Algorithms enable secure conversations where only participants know the content. WhatsApp, for instance, claims to offer end-to-end encryption, unreadable even by its parent company.

Sounds great, right? But what if WhatsApp secretly included a key to decrypt all messages? They claim no such key exists, but how do you know? You can’t see the code, key structure, or how the service operates, so you’re forced to take their word for it—blind trust. They might be truthful, fearing reputational damage otherwise.

But as the Snowden leaks revealed, companies sometimes can’t be honest. Intelligence agencies can install backdoors, and companies may be barred from intervening.

Web3’s blockchain architecture tackles this trust issue. Its openness and transparency are key. You can analyze a company’s infrastructure and operations to determine if it’s a disguised Web 2.0 operation—say, claiming peer-to-peer structure while relying on a centralized data center.

04 What Is Decentralization?

Decentralization is a cornerstone of Web3 and the internet’s original spirit, though today it’s mostly confined to technical protocols. In practice, internet activity revolves around tech companies.

For Gavin, decentralization means “anyone can as easily become a service provider or co-provider as anyone else in the world.”

This sounds challenging. It’s hard to imagine anyone but highly skilled programmers providing internet services, potentially leading back to centralization.

Gavin clarifies that having the “right and freedom to do something” is distinct from it being “fundamentally impossible.” If someone uses freely available resources to provide a service through their efforts, they’re a co-provider, and the service remains free.

“This doesn’t mean everyone needs to learn to code and become a Web3 programmer,” he adds. “I’m not trying to convince you everyone can do it. The point is, the more people who can, and the lower the barrier, the better.”

05 What Does a Web3 World Look Like?

Gavin predicts early Web3 apps will likely be incremental improvements over Web 2.0 apps. But eventually, Web3 will enable financially robust, peer-to-peer economic services—something Web 2.0 struggles with.

Cryptocurrencies are just a small piece of this, and transfers are an even smaller part. Web3’s economic services could cover rare, expensive, or complex assets.

Take a dating app as a simple example. A Web3 app might limit you to sending one digital flower per day to a match, no matter how much you pay, creating true scarcity. A Web 2.0 company, driven by profit, would likely let you send unlimited flowers for a price.

Do Web3 companies not need profits? How can they disrupt the status quo?

Gavin sees a fundamental difference between Web3 and Web 2.0 companies. In Web 2.0, technologies like programming empower users, enabling more efficient, scalable services.

Blockchain operates differently. It’s a social structure—a new set of rules that ensures no one holds arbitrary power within the system. As a user, especially a programmer, you can read the code and verify it’s doing the right thing.

You can also infer reliability from user numbers. If many people use a service or join a network with certain expectations, they’ll leave if those expectations aren’t met.

Gavin stresses that Web3 isn’t about replacing tech giants, though their concentration of power “threatens the services and expectations we have.”

“More importantly, Web3 is a broader social movement, shifting from arbitrary power to a more rational model of freedom,” he says. “It’s the only way I see to protect the free world we’ve enjoyed for the past 70 years—and to ensure it thrives for the next 70.”